This Boardcast is sponsored by Floodgate Games.

The Boardcast is audio narrations of select articles. Listen to all episodes (or find out how to get them in your favorite podcast app) here.

Prototype+ members can access an ad-free version here. You can also listen on your favorite podcast app using the private invite and link you received via email. Lost your link? Email admin@wericmartin.com.

If you've solved a logic puzzle from Belgian publisher Smart Toys and Games anytime in the past 25 years, you've probably had your hands on the work of Raf Peeters, who has created more than 130 such puzzles since 1999.

Peeters, 54, graduated from college in 1994 with a master's degree in product design, focusing on toys for his graduation project because he already had years of experience in toy design. "The only commercial toy that truly satisfied me was LEGO", he told me. "Because of that, I spent most of my childhood playing with games and toys that we invented or built ourselves", although "playing" typically wasn't the end goal.

"Often, the process of creating them was more important than the final result", says Peeters. "As a teenager, I spent every summer making a new board game, which we might play only once or twice at the end of the holiday. The next year, I wouldn't go back to it — I would simply start creating something new, so when it came time to choose a graduation project, 'toys' were the natural choice for me."

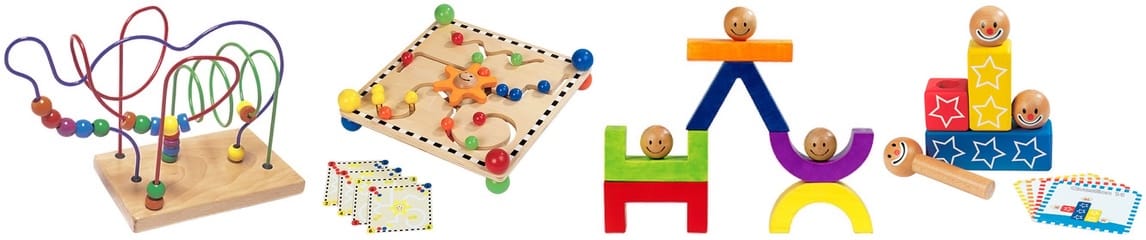

When Peeters started at Smart Toys and Games in 1997, he initially developed children's toys made of wood, wire, and beads. "For me, the most important aspect of a toy is that it is a 'tool for play'. That sounds obvious, but it actually isn't. Many toys are designed mainly as gifts or collectibles. Their primary purpose is to look impressive and make someone happy when they open the box, but if you analyze what a child can actually do with these toys, the answer is sometimes disappointing. Often, the box the toy comes in offers more play possibilities than the toy itself."

When Is a Puzzle Not a Puzzle?

Peeters' real passion, though, has turned out to be designing "puzzle games" — which are marketed by the company as "SmartGames" — with precursors to these logic puzzles being visible in the toys above: cards showing patterns that you want to create by sliding wooden dumbbells in the board's grooves; stacking circus clowns that later evolved into the logic puzzle Day & Night, which challenged toddlers to stack items to match images and silhouettes; clown-head rods and blocks that became Castle Logix.

[Editor's note: All links to Smart Toys and Games products go to a page on Raf Peeters' personal website where he explains the product's origin, how it challenges players, what he learned while developing it, why it looks the way it does, and so on. As a fan of product design, I've spent many hours reading these background stories...and now you can, too!]

Peeters uses the term "puzzle games" because "there isn't a single, universally understood word that accurately describes what SmartGames are. Terms like 'brain games', 'thinking games', 'brainteasers', or 'logic puzzles' all come close, but each can also mean something different from what I create. For example, in Dutch there is no separate word for 'jigsaw puzzles'; we have only the word 'puzzle', so if I simply said that I design 'puzzles', many people would assume I make jigsaw puzzles. A more accurate description would be: 'a single-player puzzle game with multiple challenges that range from easy to difficult', but that's more than a mouthful and not very practical in a description."

He continues, "To me, a typical puzzle is a problem with a predefined solution that the player can find using their ingenuity — and because it's a game, looking for the solution should of course be fun. In contrast, a board game creates new problems continuously and the outcome is not predefined; each player introduces a new challenge for the opponent every round. A good game stays exciting because the tension builds naturally as players get closer to winning. The variation comes from randomness in the game mechanics and/or the fact that the actions from the opponent(s) are not 100% predictable."

"In a SmartGame, I function as the 'opponent' to the puzzler. However, since there is no end goal of winning, every individual challenge must increase the level of excitement on its own in order to keep the experience engaging. This is one of the many reasons SmartGames are structured with a gradual progression of difficulty."

Making Things Hard for Yourself...and Others

The notion of progressively increasing challenges was already present in logic puzzles such as Nob Yoshigahara's Rush Hour, which debuted in the U.S. from Binary Arts in 1996, but SmartGames has formalized this practice with hard-coded difficulty levels. These days almost all such titles feature 60 or 120 challenges, with 12 or 24 challenges in each of five difficulty levels.

"For the past ten years, I have defined for myself what each level should be," says Peeters. "For games playable by children of age 7 and up and by adults, the average time needed to solve a challenge — after set-up — is as follows:"

- STARTER: less than 30 seconds

- JUNIOR: less than 1.5 minutes

- EXPERT: less than 5 minutes

- MASTER: less than 10 minutes

- WIZARD: more than 10 minutes

How do you figure out which puzzle belongs at which level? Testing is key, with Peeters pointing out that Smart uses a pool of "average" puzzle solvers to represent the audience at large: "I once had a playtester who could solve any challenge almost instantly. His results weren't useful because all his timings were nearly identical and mostly reflected the time needed to physically place the pieces."

The times are approximations, of course, with some testers having experience with past puzzles and applying strategies they've already learned and with some being new to this type of challenge. "Don't feel bad about yourself if you need more time than mentioned above," says Peeters. "It doesn't make you any dumber. These times are simply a metric we use to keep difficulty levels consistent across different games and to ensure that all SmartGames offer a comparable total playing time — and therefore similar value for money."

What's more, says Peeters, "this also means that if you can’t solve a challenge at the Wizard level, you are perfectly normal. Most people can’t. In fact, most people give up — or start throwing puzzle pieces — long before solving these very hard challenges, myself included. We added the Wizard level mainly to prevent most players from completing all challenges, and to satisfy the relatively small group of players who want to explore the hardest challenges possible. Personally, I find the Expert and early Master levels the most interesting: they are difficult enough to be engaging, yet still provide enough clues to be solved logically. Wizard-level challenges often feel more like trial and error, and solving them usually requires a great deal of patience, perseverance, and luck."

I did a double-think at Peeters saying the company wanted to prevent solvers from completing all challenges, but in a way this is akin to how publishers include oodles of expansions, promos, freebies, and upgraded bits in crowdfunding projects. Only a few people will experience all of these items in play, but they're part of the package and suggest that there will always be something new to explore...regardless of whether you'll actually get to it.

In this case, Wizard was added as a difficulty level in 2016 as Peeters' boss wanted to have five colors in the Smart logo: "Some of the games before 2016 also have challenges that are hard enough for a fifth level, but they show only four."

Additional challenges were added — IQ-titles, for example, went from 100 challenges to 120 — so that the SmartGames had as many challenges as before, with those Wizard-tier efforts being out of reach for most solvers. "Before 2016", says Peeters, "we regularly received feedback from customers who played all the challenges of a specific game and asked if they could get more challenges (of course, for free). Since we've included this Wizard level, we no longer receive this kind of question."

Sorting the Pieces

The difficulty level format used throughout Peeters' puzzle games helps them feel like a consistent product line, giving buyers confidence that if they enjoy puzzle A, then they'll probably like puzzle B — but of course not all puzzle games are the same.

"Early in my career, I worked largely by intuition," says Peeters. "I just tried to create a few new games every year. Over time, I started seeing patterns. I realized that I was repeatedly returning to the same underlying mechanics, simply exploring them in different forms. Eventually, I identified five core puzzle concepts that consistently work well for SmartGames. Puzzle collectors might argue that there are many more puzzle categories — and they would be right. However, many of those categories are not well suited to SmartGames' core constraint: a single set of pieces must support a large number of challenges, ranging from very easy to very difficult. The five categories I've identified (so far) are these:"

1) Matching Puzzles: The player's task is to reproduce a given image or configuration. In a sense, the solution is already visible at the start, though often incomplete. Tangrams are a classic example. At SmartGames, this mechanic is mainly used for preschool titles such as Bunny Boo and Safari Park Jr. From a design perspective, matching puzzles are ideal for young children because the rules are minimal and immediately understandable.

2) Packing Puzzles: This is the largest and most obvious category, and what most people think of when they hear the word "puzzle". The objective is to fit a set of pieces onto a game board or into a grid, in either 2D or 3D. All IQ puzzles I've made, such as IQ Twins and IQ Noodles fall into this category. People like these games, probably because they are self-explanatory and not much can go wrong. If everything fits, the solution is correct, so there's also no need to double-check. The only reason I've designed so many different packing puzzles is because this is by far the most popular category.

3) Pure Logic Puzzles: These are similar to packing puzzles, but the constraints come from the rules rather than the physical shape of the pieces and game board. You could say that in packing puzzles, the challenge is defined by the "hardware" (the shapes and positions of the pieces), while in logic puzzles it's defined by the "software" (the rules). Pieces can physically be placed anywhere, but only certain placements are allowed according to the rules or the specific requirements of the challenge. Games like this often target an older audience because the rules are more complex and you always have to check your solution afterwards — but I have made a few pure logic games for kids, like 5 Little Birds and LogiBugs.

4) Connection Puzzles: These combine elements of packing and logic puzzles. The goal is to place pieces on a board in such a way that they create a connection between a starting point and an endpoint. I treat this as a separate category because it leads to visually distinctive games, often involving pathways. Examples include Smart Dog and Little Red Riding Hood, but the concept isn’t limited to roads or paths — it can also involve marble tracks, ropes, or even laser beams, anything that creates a connection. These games are somewhat related to the next category of sequential movement puzzles since they also feature a clear start and goal.

5) Sequential movement puzzles: This category is fundamentally different from the others. While the previous types are relatively static, sequential movement puzzles are dynamic. The goal is to move one or more pieces from a starting position to an end position. In these puzzles, the sequence of your moves is crucial, hence the name of this category. This is my favorite type of puzzle, probably because each challenge feels more like a small adventure than a puzzle problem. If the other categories deal mainly with 2D and 3D space, this one adds a fourth dimension: time. The step-by-step game mechanic also feels a bit like playing a board game. Many people find these puzzles more difficult because they have more problems developing solving strategies for them (beyond trial and error). SmartGames like Snow Problem, Jump In', Squirrels Go Nuts!, Cats & Boxes, and Temple Trap are all sequential movement puzzles and games that are in my personal top 10.

Peeters' says, "At an abstract level, nearly all single-player puzzle games — ours and those of our competitors — can be mapped onto one or more of these five categories. This doesn't limit variety. Within each category, there is still enormous design space. For example, sequential movement puzzles can be built around sliding, jumping, stacking, tilting, or other movement systems, each producing a very different experience."

"Finally, most games don't fit neatly into just one category. Many puzzles combine multiple mechanics, such as packing and logic rules, or begin with a set-up phase that involves matching what's shown in the challenge. Whenever possible, I also try to introduce different mechanics across difficulty levels to give each game enough variation and keep it interesting throughout."

Setting Boundaries

Whatever the puzzle format, Peeters aims for simplicity, while striking a balance between possibilities and restrictions. "For me, complexity should be the result of how all elements in a game interact with each other. If you choose the right pieces and the right rules, you don't actually need many to achieve an interesting complexity." To rephrase that in the form of a mantra:

A puzzle game with limited pieces and rules needs enough freedom to allow solutions, but also enough constraints to make those solutions interesting.

How do you find that balance? The number of solutions for a puzzle design is a good starting point. If that number is low relative to other puzzles you've created or encountered, perhaps you have too many restrictions, too few pieces, the wrong type of pieces, or another design element that you can tweak. Says Peeters:

Restrictions can take many forms: the shapes of the puzzle pieces, the outline of the game board, or — in sequential movement puzzles — the rules governing how pieces are allowed to move. When a puzzle concept is too restrictive, you experiment with different sets of pieces or rules that offer more options. Sometimes changing the shape of a single piece can turn a puzzle with only a few solutions into one with hundreds of thousands. For that reason, I try not to abandon an idea too quickly if the first version doesn't produce enough possibilities. Other ways to increase options without adding more pieces or rules include making pieces double-sided or allowing them to transform, as in Penguins on Ice and Treasure Island.

On the other hand, too many possibilities removes the challenge altogether — or at least makes it impossible to create puzzles with a unique solution. This is one reason most SmartGames avoid boards larger than 6×6 or 5×10, and why the number of puzzle pieces is often fewer than twelve. There is a sweet spot. If you increase the board size or the number of pieces too much, you mainly make the set-up harder because more fixed pieces will be needed in order to maintain a single, unique solution.

In his early years, Peeters experimented continually, sometimes succeeding, sometimes not, but after more than two decades he's developed enough experience that he can more intuitively recognize how to make his way to that balancing point between possibilities and restrictions. "That said, too much experience can also be limiting. This is why working with younger colleagues is so valuable. They sometimes repeat the same mistakes I made in the past — but they also regularly surprise me by trying things I wouldn't even consider anymore. The best moments are when someone proves you wrong because those are the moments when you truly learn something new. My ego can handle the fact that I am not always right..."

He adds, "Early on, I also tried too hard to be 'original'. Over time, I learned — sometimes the hard way — that it's better to create something that works than something that merely feels novel but isn't necessarily better. That's why I prefer the word 'distinct' over 'original'. On an abstract level, I know that the core mechanics of my games aren't always entirely new, but I make sure they look and feel clearly different from other games on the market. In fact, some of my most original games have been the worst sellers simply because consumers didn't understand them, so there is another balance to strike here: between familiarity and innovation."

Leading the Horse to Water

As for creating the individual challenges for a particular puzzle design, Peeters and the Smart team start with thousands of possibilities — then throw most of them away. As he wrote about IQ Fit, "There are 150,675 ways to [fill the grid], but we made a selection of the 120 most interesting for the challenges in the booklet."

How do you determine which .1% of the challenges survive? To start, look for the outliers. "My first step is to search the dataset for rare or unusual set-ups or solutions", says Peeters. "These can take many forms — for example, a challenge that provides only a single piece as a starting hint. Or if among thousands of possible challenges, only a few have a specific piece in a particular position, I make sure those rare cases are included in the final selection."

"Another important factor is visual appearance. An algorithm doesn't care where pieces are placed, but humans do. Solutions or challenge set-ups that look symmetrical or form interesting patterns tend to feel more special and less random, so I actively look for challenges that visually 'stand out'."

I noticed this while working my way through IQ Twins, a packing puzzle with five pairs of pieces, each pair having a different color. One member of each pair is placed in the grid at a 90º angle, while the other member is placed at a 45º angle. The STARTER challenges in IQ Twins use all of the 90º pieces, the JUNIOR ones all the 45º pieces, the EXPERT ones have two pairs of pieces, and the MASTER ones have a single pair. (The WIZARD challenges have no set pattern, but as Peeters noted above, solvers who work their way through WIZARD challenges are a special breed who probably care more about difficulty than aesthetics.)

As Peeters and the Smart team develop the set, they look for what's missing from the challenges already chosen, trying to include as many types of challenges as possible. "This iterative process helps create the best set of challenges", he says, with the important part of this sentence being "best set". As Peeters suggested earlier, the strength of a design like this isn't the novelty of an individual challenge, but how the challenges develop an experience over time.

"When the dataset is very large", says Peeters, "there are of course many equally valid ways to assemble an interesting set of 120 challenges." That selection process is as important as the design of the puzzle itself. "It’s easy to assume that when thousands of challenges exist, the specific selection doesn't matter much. In reality, different types of solutions are rarely distributed evenly. If challenges are chosen randomly without additional criteria, the result is usually a set filled with very similar, boring puzzles, while many of the most interesting and distinctive ones are left out."

Peeters explains that the difficulty of a challenge results from a number of factors, some of which are obvious and some that will invisibly guide the solver:

• The number of hints (for matching, packing, logic, and connection puzzles). More hints generally make a challenge easier — but not always.

• The number of steps required to reach a solution (for sequential movement puzzles). Solutions with more steps are generally harder — but not always.

• The quality of the hints. Fewer hints are often stronger because they include more meaningful information. Otherwise, the challenge wouldn't result in a unique solution. Stronger hints, of course, tend to make a puzzle easier. For example, in a packing puzzle, a single piece placed in the center of the board can be more helpful than four or five pieces neatly arranged in a corner.

• How surprising the solution is. As players become familiar with a game, they start to see patterns and develop strategies that usually guide them toward the solution. For higher difficulty levels, I deliberately try to include challenges that break these expectations. Of course, the fact that a challenge introduces a new and unexpected solution heavily depends on the nature of the challenges that preceded it. Therefore, this is not a characteristic of a specific challenge, but rather of the entire set of challenges.

"My colleagues in the IT department would love to develop an algorithm that can perfectly predict difficulty", he says, "but we're not there yet. Every new game introduces its own variables, and by the time we fully understand which criteria matter most, the final set of challenges has usually already been selected."

This brings us back to playtesting. In a packing puzzle, a computer can try every possible combination of pieces for any given set-up in seconds, which doesn't replicate how people will approach solving a puzzle. "There are always a few challenges that turn out to be much easier — or much harder — than expected", says Peeters. Maybe a puzzle needs extra hints to get solvers past a sticking point, or maybe you need to re-assess how difficult something is. "With Cats & Boxes, I had to revise the challenge set three times before achieving the right balance as each time, the challenges turned out to be harder than I expected."

That said, sometimes challenges are "harder than expected" because the solver has inadvertently made it more challenging for themselves. "Each game requires its own set of strategies, and it's up to the player to discover which ones work best", says Peeters. "We carefully select challenges in the easy levels that teach these deductive techniques so that players are prepared when they reach harder ones. Many adults skip the STARTER and JUNIOR challenges only to find the EXPERT level far more difficult than expected — not because the challenges are unfairly hard, but because they missed the opportunity to learn the necessary strategies along the way."

Trial and error is a valid way to solve logic puzzles, but as the challenge difficulty increases you reach a point where error becomes the default result. "There are simply too many options to try", says Peeters.

Deduction and learned solving strategies become necessary, but they won't always get you the solution. "In an ideal world, you should be able to deduce all challenges," says Peeters, "but in reality, this is not possible for the hardest challenges. One valid strategy that we try to encourage is to 'look for hidden information'. The physical appearance, game rules, and the challenges are the 'shown information', but in a good puzzle game there are always extra hints you can deduce from this given information. A favorite example of this can be found in most packing puzzles. If the rules state that a challenge has only one solution — as is the case with most SmartGames — then any partial arrangement of pieces that can be flipped, mirrored, or rotated into another valid arrangement must be wrong. If such an arrangement were allowed, the challenge would have multiple solutions. Recognizing this lets you eliminate many options early and find the solution more efficiently."

Picking the Next Piece

In a February 2024 interview with Mojo Nation, Peeters said that aside from the 130+ published single-player SmartGames, he had "around 80 still in production", which struck me as an astonishing feat — but he clarified to me that "in production" covers a wide range of steps.

"My work actually consists of two very different roles. The first is inventing — coming up with new ideas. The second is product development, which is what I was trained for as a product designer. In many toy companies, the inventing part is done by external inventors because it's messy, unpredictable, and difficult to fit into corporate schedules. How long does it take to come up with a good idea? Sometimes five minutes, but more often ideas sit in my head for years before I feel they are strong enough to develop. And most ideas never reach that stage at all — they simply remain ideas."

I've heard the same thing from many designers over the years. Someone starting out as a designer might think the key to success is a good idea, but the idea is at best a skeleton — a framework that can support the weight of the final product but little of merit on its own.

Once Peeters is confident that a puzzle game can generate enough challenges at all difficulty levels and that it can be presented in a "visually distinctive or iconic" manner, he pitches the idea inside the company. If his colleagues are convinced, with the creative department having about twenty people out of 150 total employees, development starts, with the process taking about a year to go through these steps:

- Calculating possible challenges. My colleagues write algorithms to do this. We often test different sets of puzzle pieces and/or rules to see which combinations produce the best results.

- Creating the game's 3D design using software such as SolidWorks or Blender and making 3D printed prototypes.

- Creating, testing, and selecting challenges, and arranging them in the correct order of difficulty.

- Developing all remaining product elements, including photography, the rules and commercial text, and the packaging and challenge booklet.

- Presenting the finished games to professional audiences — such as retailers — at toy fairs like those in New York and Nuremberg.

- Following up on user feedback. Sometimes this means correcting errors or rewriting rules. Most games stay in production for many years, but occasionally we also update packaging artwork or make other improvements.

"In an ideal world, we would already be working on products planned for 2028", Peeters told me in January 2026. "In reality, we are still finalizing details for some 2026 releases and have just started development on items for 2027. As a result, every year feels like a race against time. Even after more than twenty years, there is still room for improvement in this area. That said, planning too far ahead also has its risks — you need to stay flexible enough to respond to changes in the market. While SmartGames doesn't chase short-lived trends, the games we develop today are different from those we made ten years ago."

"The inventing part is the only aspect I do entirely on my own", Peeters continues. "Everything else is the result of close collaboration with colleagues from different departments. For example, over the past twenty years, I worked closely with Leighton Rees on the 3D design of our games. He sadly passed away last year and will be deeply missed — not only as a friend, but also for the unique contributions he brought to our projects. Inventors often receive most of the attention, but everyone involved in the process plays an essential role. As the saying goes, 1 + 1 = 3 — and that was certainly true for the work we did together."

Peeters regularly receives feedback from the public for that work, and his joy from doing so is a reminder that we should all pass along our appreciation to creators more often. "This still surprises me every time, but I'm very grateful for it. Knowing that my work mattered to someone — even if only for a few hours of their life — enough that they took the time to write and say thank you is one of the most rewarding aspects of my job."