The Boardcast is audio narrations of select articles. Listen to all episodes (or find out how to get them in your favorite podcast app) here.

Prototype+ members can access an ad-free version here. You can also listen on your favorite podcast app using the private invite and link you received via email. Lost your link? Email admin@wericmartin.com.

While working at BoardGameGeek, I'd often dip into the game submission queue to approve a pending game listing to link it in a BGG News post or because a publisher had already announced the game and asked whether their pending submission could be bumped to the front of the line.

Often, though, I was just trying to help other admins clear out the queue. Game submissions to the BGG database ebbed and flowed, often ballooning in the month prior to Gen Con or SPIEL, then I'd suddenly notice five hundred pending submissions and think, hmm, maybe I should lend a hand there.

One constant presence in the game submission queue, no matter the time of year, were submissions inappropriate for the BGG database, specifically puzzles. Hardly a week would pass without someone submitting a listing for Rush Hour, a logic puzzle by Nob Yoshigahara that debuted in the U.S. from Binary Arts in 1996 and that has been in print ever since. We'd decline that submission, decline the next one, decline, decline, decline — yet those submissions kept coming.

BoardGameGeek prohibits puzzles in the database, in addition to prohibiting drinking games, conversation games, electronic games, prognostication tools, and most structured activities, in order to keep a boundary around what's listed. If BGG adds a listing for Rush Hour, then why not a wooden sliding puzzle with a similar goal, why not the Soma cube, why not metal horseshoes linked with a chain in which you need to free a trapped ring, why not a cryptogram in which you similarly need to find the "key" to unlock the solution, why not jigsaw puzzles and crosswords?

The Twain Shall Meet Over and Over Again

The line between game and puzzle is difficult to judge and has only became harder over time as designers and publishers release titles that blur that line even further. To pull out a historical example, let's look at tangrams, in which you're shown a silhouetted image and challenged to recreate it with seven polygonal tiles. This is clearly a puzzle, yes? Designer Geoff Engelstein would argue it is. "Fundamentally," he says, "I see a few defining characteristics of puzzles vs games:"

1) Puzzles are "one-time" activities. If you solve a puzzle, there is no reason to go back to it to solve it again.

2) Puzzles have a correct solution.

3) Puzzles generally have no loss state. You just keep working on them until you get the solution.

Tangrams exhibit all three of these characteristics...but what if someone packaged two sets of tangram tiles together and players now raced to recreate an image with their own set of tiles, with the first player to do so claiming a point? (This is what Maurice Kanbar did when creating Tangoes, which debuted in 1980.) Boom, you've just gamified a puzzle...and you can do that for every puzzle in existence, smashing together puzzle atoms to form game molecules.

Grzegorz Rejchtman's game Ubongo!, which debuted in 2003, is a prime example of this practice, with players using an identical set of pieces to recreate a shape (a puzzle atom akin to tangrams) as quickly as possible in order to gain a reward (thus creating the game molecule containing that atom). Designer Elizabeth Hargrave suggests Cryptid, Things in Rings, and The Search for Planet X as other games that work similarly since they all have correct solutions not affected by user input.

The escape room games that started to appear in the mid-2010s, such as Escape the Room, EXIT: The Game, Unlock!, and Deckscape, are another example of this blurry line between game and puzzle. In either a physical escape room or one of these games, you're presented with puzzle challenges, and as you complete them, you gain a new puzzle, a tool to help solve an earlier puzzle, or another reward.

So this escape room is nothing more than a series of puzzles, yes? If you started again, you'd know all the answers and could blitz through the puzzles, solving the overall challenge more quickly than before...and yet that element of spending time to reach the goal is what transforms a series of puzzles into a game because time spent playing can be translated into a score or a win/loss condition.

"I have found it helpful to think of a 'puzzle' as a challenge with a single solution and no constraints on how you might go about solving it", says designer Phil Walker-Harding. "Once you add constraints, such as a time limit, I can see why you might then characterize this challenge as a 'game'." Clearly BoardGameGeek agrees, which is why EXIT: The Game, Unlock!, and the like are all listed in its database.

However, whatever characteristics you ascribe to puzzles to fence them away from games prove inadequate because counterexamples are plentiful. "It is often said that puzzles have one optimal solution", says designer Paul Schulz. "But if that were a defining property, Ubongo!, Ghost Blitz, and Dobble all are a series of puzzles — and so is every single trivia game. Surely, gamers would protest this categorization."

He continues, "Another typical feature I hear about puzzles is that they are solved with logic, but that's often not true: Crosswords are often just trivia questions, while word searches, mazes, and jigsaws are perception or concentration exercises — no logic there. Still, all of them are called puzzles. The game examples I gave earlier seem to be gamified by competition, but solving the crossword with a time limit or against one another still wouldn't qualify it as a game for most of us."

Engelstein even suggests that crosswords as they already exist break his criteria for differentiating between a puzzle and a game. "If I am doing a crossword puzzle in a magazine, I would have to look at the answer to see whether I solved it or not, which means I do 'fail' or 'succeed' in figuring it out. Crossword software gets around that a bit by letting you know whether you're right or not, but not showing the answer. A sudoku puzzle or cryptogram, on the other hand, is 'self-checking' in that you can determine whether your answer fits the criteria without an answer key."

In short, says Schulz, "The categories of games and puzzles do not just overlap. Their borders are inconsistent."

Going Deeper

Wei-Hwa Huang is the co-designer of Roll for the Galaxy; has worked on many logic puzzles for ThinkFun, such as Gravity Maze; won the 2008 Sudoku National Championship; and is a four-time winner of the World Puzzle Championship, so he has deep experience in both games and puzzles — and he explained to me that as with so many other things in life, "puzzleness" isn't a binary state of yes/no, but a spectrum.

He said, "Like many terms, I try to strike a balance between 'I know it when I see it' and 'Here's a comprehensive definition', so given that I'm open to exceptions, here's my definition of a puzzle:"

A puzzle is an activity with an intended and specific path to a goal (often called a "solution"), where using intelligence is the primary part of the solution-finding process. Some salient parts of this definition:

• The less specific the solution path is, the less puzzle-like the activity is. If I give you a bunch of popsicle sticks and ask you to build a bridge that can handle a one-pound weight, some would consider that puzzly, but I'd consider that more like a "puzzling problem" or a "design challenge".

• If there is no intended solution path, it becomes less "puzzle-y" and more "problem-y". A game of Pandemic, for example, has puzzling aspects, but since the set-up is based on random card shuffling, I don't consider playing a game of Pandemic to be a puzzle. On the other hand, one could imagine providing players a specific ordering for the cards in Pandemic that was carefully selected such that there are only a limited number of ways to win, and the players are allowed to play with that repeatedly until they win. I would consider that a puzzle despite the rules being identical to Pandemic.

Perhaps a more well-known example is chess problems of the nature "White to play and win in 3 moves", where the player has to think through the different possible chess moves to find a single intended solution — and that solution is usually not in alignment with general chess strategy. Although traditionally those are called "chess problems", I would consider them "chess puzzles", whereas a "chess problem" would be "Here's a position from a real chess game. What's the best move?"

• Using intelligence is important for the term "puzzle" to work. Finishing a level of Pac-Man or beating an arm-wrestling robot might have a goal and an intended and specific path, but aren't generally considered puzzles.

• I'm somewhat on the fence as to whether "having fun" is an important part of being a "puzzle". If neither the person designing the activity nor the person playing the activity intend for it to be fun, is it a puzzle if it qualifies for the other goals?

Given that “having fun” is relative from one person to another, it might seem odd to think about defining puzzles based on the "vibes" that solvers have when confronting them, but Phil Walker-Harding leans into that notion. "Most of these definitional discussions about what is and isn't a 'game' can be interesting thought exercises", he says, "but I don't think much is gained by trying to lock things in too neatly or by being dogmatic about it."

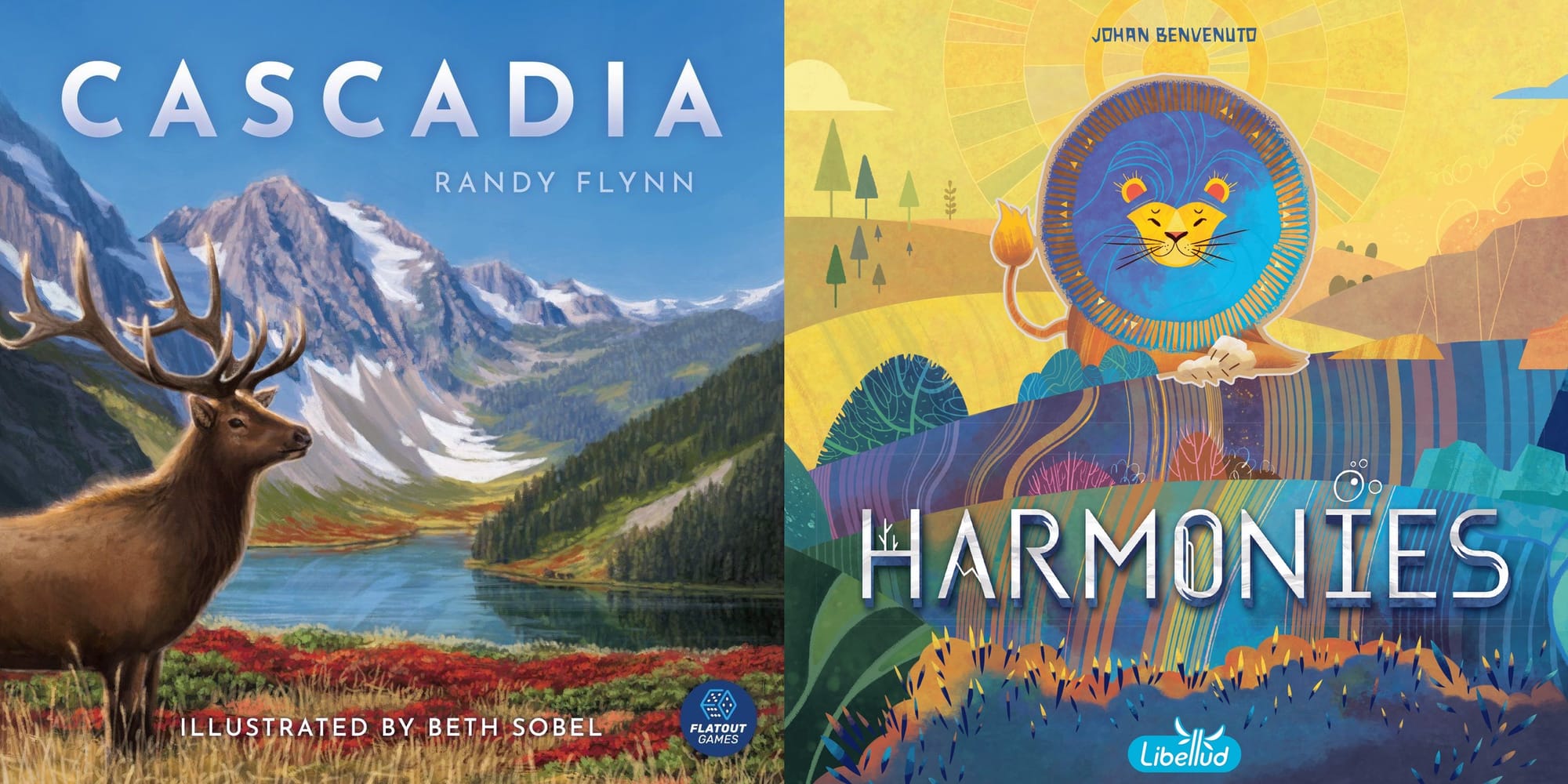

He continues, "For me, I think this distinction is interesting when considering the appeal of games in the 'take and make' genre such as Cascadia and Harmonies. Here, I notice a lot of people use the word 'puzzly' to talk about making decisions on their turn. I think this is insightful because the thought process you are going through when placing a piece is similar to doing a spatial logic puzzle. However, because there isn't one single solution (since you may arrive at a winning score in many different ways) and because you don't have complete information about future events (such as which pieces your opponent will take), this isn't a pure 'puzzle' but more a 'puzzly game'."

More Than a Feeling

Elizabeth Hargrave has a slightly different take: "When we say certain games feel puzzly, I think it's often in the sense that there is a single best play or series of plays (and maybe a few more that are only slightly sub-optimal), that this can be figured out, and that the figuring-out can feel like its own reward. I have absolutely nothing against games that are solidly in the puzzle category — in fact I love them — but if you want to make a game that's not a puzzle, you need to be looking for an outcome that's not fundamentally 'Did you find the one answer?'"

One way to do this is to put players in charge of what that "one" answer is so that the lone answer differs with each playing. Hargrave gives Just One, Caution Signs, and So Clover! as examples of games in this category, while Paul Schulz suggests Codenames, Decrypto, Krakel Orakel, and Concept. Says Hargrave, "There's still a single correct answer, but user input is now changing how you get to that answer, and just like I ignore the timers in timed puzzle games, I ignore the scoring rules in these puzzle party games. It's just satisfying to figure out the answer."

That concept of "satisfaction" plays into Hargrave's sense of how a puzzle differs from a game, even though she'd label all of the former as an example of the latter. "I like the broad definition of a game as a system of rules that creates an artificial struggle that we can undertake for our entertainment. By that definition, I would lump all puzzles as a subset of games."

"The thing that makes puzzles a definable category within games (or some would say, the thing that separates them from games)", she says, "is that they have a fixed correct answer and a more or less fixed path (or set of paths) for arriving at that answer. No amount of input by the puzzler will change this; the only question is whether you will find the answer and win — and my personal experience of this win state is often so satisfying that any attempt to gamify it beyond 'You win!' feels tacked on." (Along these lines, Hargrave gives a shout-out to A Carnivore Did It!, calling it her "favorite find of SPIEL Essen 2025". This design by Daumilas Ardickas and Urtis Šulinskas consists of two thousand logic challenges, and the only reason you'd consider it a game is because of time limits suggested in the rules.)

That "You win!" feeling brings us back to vibes being a core element of a puzzle. Along these lines, Paul Schulz says, "It could be like the fruit versus vegetable discussion: They're not different by nature; it's about how we use them. If our focus is on solving for the sake of solving, it's a puzzle; if our focus is on other things, such as competition or an overarching story (as in EXIT) it's more likely a game."

Both Wei-Hwa Huang and Geoff Engelstein call out Manuel Rozoy's T.I.M.E Stories as a design that uses story to blend puzzle and game in a unique way. An episode of T.I.M.E Stories typically has an optimal path through a loop, something common to puzzles, while featuring random elements like player choices and dice rolls to resolve combat. Players can fail an episode in a multitude of ways, losing the game, yet they can restart from the beginning, using past experience to do better. Says Engelstein, "The looping nature makes it feel more like a game, and it does have a loss state, but it also has an optimal path and there is no reason to play a case again."

Recently I've come to think of games as being akin to improv, with the actors being fed a setting, roles, and basic rules for interaction, then let lose to play off one another, whereas puzzles as akin to plays in which you have scripted lines and directions for how the action is supposed to be carried out on stage — although improvisation will often happen thanks to mistakes and chance. Performers of both plays and improv can find great satisfaction in what they do, and bystanders can appreciate the skill of performers in either role, so it's not like one is superior to the other.

Says Schulz, "Including puzzles with games goes along with my favorite definition of games: 'the voluntary overcoming of unnecessary obstacles'." Bernard Suits used this definition in his 1978 book The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, and having a broad definition like this for both games and puzzles seems ideal for designers and players alike, giving everyone a wider stage on which to create and perform as they wish.